Common Names

For many, one of the most frustrating things about observing spiders is the fact that most species are not referred to by “common names.” These easy to remember English names have been given to all bird species, butterfly species, as well as many other creatures familiar to us.

Only a few spiders have been given such names. There is actually an official committee (Committee on Common Names of Arachnids of the American Arachnological Society) that was created to provide standardized English names for species of arachnids of medical or economic importance, or those common enough to be familiar. Anyone who has given a talk on spiders to a general audience will immediately recognize the value of common names. Trust me, I’ve given more than my share of programs punctuated by names such as “Parasteatoda tepidariorum” or “Agelenopsis pennsylvanica.”

Most spider species are tiny and inconspicuous. Well over half of the described species in North America north of Mexico never achieve a body length greater than 2 or 3 mm (~1/16 – 1/8 inch). These little spiders are so difficult to see well that, even if we gave them descriptive English names, the features implicit in the name would be too inconspicuous to notice. They simply wouldn’t be useful, even for experienced naturalists.

But, as the existence of the aforementioned committee implies, some spiders do have useful English names that are commonly used. Here are a few examples.

The bowl-and-doily spider is the first spider common name that many of us learned. The phrase bowl-and-doily refers the iconic web of this species. It does indeed have a bowl shaped sheet web, suspended over a relatively flat lacy sheet web.

There is actually more to this web than the obvious bowl and doily. There is also a non-sticky tangle above the bowl. The purpose of the tangle is to intercept the flight of potential prey. When a hapless fly blunders into the tangle, it is often knocked out of the air and tumbles down to the surface of the bowl. The vibrations of this motion are detected by the resident spider and she is usually waiting just below the bowl precisely where the fly lands. In a flash she strikes up through the silk web and envenomates the fly. This is not a fair contest and the fly is quickly killed and drawn through the bowl to provide a feast for the resident spider. Here is another photo of such a web taken on a particularly dewy morning that reveals the tangle above the bowl.

The resident spider is relatively small. She is most often found hanging below the web. Her dark coloration with white bands is actually somewhat cryptic in this situation.

For a close-up view, here is an illustration of her from Common Spiders of North America drawn by Steve Buchanan.

If you are lucky enough to encounter a courting pair, the male often stands out in contrasting reddish coloration. The following beautiful photo was made by Sarah Rose. In this case the red male is closest to us with his potential mate in the back.

So why the quaint name “bowl and doily?” This is actually a fairly old common name. It dates to a time when finding a bowl of candy sitting on top of a crocheted doily would have been commonplace in your grandmother’s parlor. The name is based on the fancied resemblance of the web to this scene. I staged this “re-creation” below.

Here is another example of a common name based on a distinctive web. The filmy dome spider (Neriene radiata). Her web is usually built in the forest, often in the shady understory. The web is composed of very fine silk strands and is quite delicate. It can be difficult to see the web at all. But when there is enough dew condensation the dome shaped sheet is revealed.

Here is a more dramatic photo by Alan Knowles. He found the spider on a very dewy morning and photographed it with a flash. You can see (if you look closely) that the spider is resting under her dome near the top at the left side.

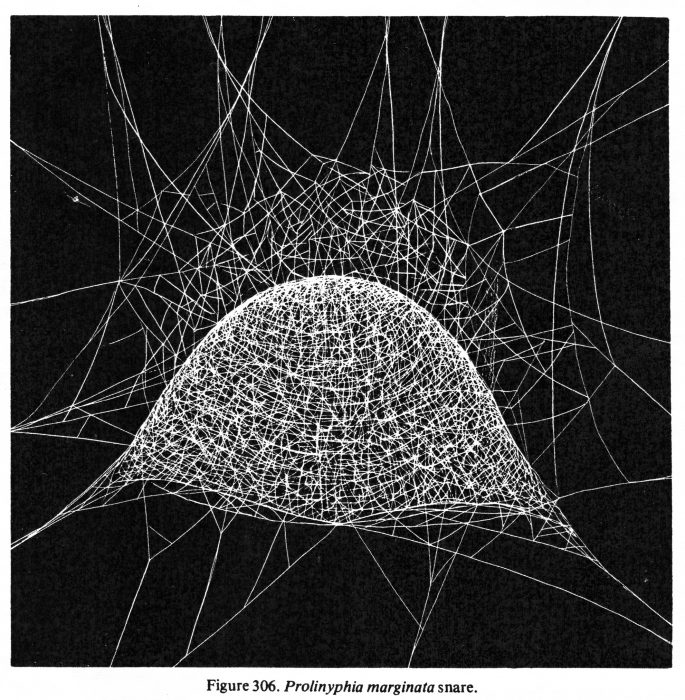

Here is the illustration from B.J. Kaston’s classic How to Know the Spiders. It reveals not only the dome but also the tangle of knock-down strands above the web.

The occupant of this beautiful delicate web is another small sheet-weaving species Neriene radiata. The sharp-eyed reader will notice that the species scientific name has changed since B.J. Kaston’s book was first published (1953, 1972). Here is a female filmy dome spider hanging in her (invisible) web.

And here is another photo made by Sarah J. Rose of a pair sharing a dome.

When the pair come together to mate the male reaches out with his palp and transfers sperm into her gonopore on the ventral side (at the top in this pose) of her abdomen. In this photo you can see the expanded hematodocha at the tip of his palp. The fluid that inflates this bag-like structure is not the semen. It is actually hemolymph fluid (blood) and the pressure from this inflated sac squeezes the actual semen out of its reservoir and into the female.

Here is a close up illustration of a female filmy dome spider from Common Spiders of North America.

Here is a third sheet-weaver example of a common name derived from the web structure built by the spider. This one is called the hammock spider based on a fanciful interpretation of the sagging sheet suspended from branches at the edges. I’ll include a photo of a web and also a real hammock for comparison, you be the judge.

The hammock spider is quite a bit larger than either of the others described above. She is a striking spiny-legged spider with a distinctive jagged dark band down the middle of her abdomen. and a dark central mark on the top of her cephalothorax that splits into two lines near the eyes.

hammock spider (Pityohyphantes costatus) female eating a prey item in a retreat under a culvert at the edge of her web

Another close up from Common Spiders of North America.

Early in the spring (at the time I’m writing this) the hammock spiders are usually hiding in a loose silken retreat under a leaf. These individuals are often sub-adult (one molt away from maturity). With the arrival of truly warm days they will construct their webs, perhaps capture a few insects and then molt into the adult. I’ve captured adult females in Ohio between late May and mid September. Most of the individuals I encounter in the late autumn, winter, and early spring, are immatures.

My last example of a spider with a common name based on a web is the lattice orbweaver (Araneus thaddeus). This spider is normally hidden from view. They hide in a tightly folded leaf retreat. The entrance to the retreat is a tubular silken structure with walls that appear a lot like the criss-cross pattern found in lattice work. In this first photo you can see the orb itself, which is connected to the retreat by a “signal lines” which transmit vibrations to the spider. If she detects that a prey has been captured in the orb, she rushes out to grab a meal.

The spider is waiting well back in the retreat.

Here is a shot of the signature “lattice” of the retreat entrance tube.

Maybe it takes a bit of imagination, but I can see a resemblance to a garden lattice.

Even if you don’t recognize the lattice pattern, you will be rewarded well if you glimpse this beautiful little orbweaver. She is one of the most widespread species in Ohio, but because she doesn’t usually expose herself in the open, she isn’t as familiar as some others.

Sometimes common names are given to a group of very similar, or related, spiders. For example the grass spiders (the 13 species of Agelenopsis, family Agelenidae). These spiders are familiar because they build webs at the edge of lawns or near trails. On dewy mornings, condensation makes the webs conspicuous. The web has an obvious funnel-shaped retreat where the spider is lurking.

It is tough to identify which species of grass spider lives in the web, but at least this name gives you a useful handle for your observations. In this case, the occupant was the most common of the five species of grass spiders found in Ohio, Agelenopsis pennsylvanica. Here is a photo of this species.

As of this post, there are 80 common names for spiders in Ohio, roughly 12 percent of the 653 species known for our state.

Sources:

Kaston, B.J. 1978. How to Know the Spiders. WCB McGraw-Hill, Boston, 272 pp.

Comments

Common Names — No Comments